Black Excellence: A Short History of Black Sororities and Fraternities

The Divine Nine (D9) is the example Black collective.

Incredibly rich in history—they’re dedicated to not only improving themselves and their legacies, but the entire Black community. They’re a line of the first nine Greek-letter Black sororities (4) and fraternities (5) that were founded in the early 1900s. They had the idea that Black voices in colleges and universities should—not only be heard—but amplified by connecting with other Black students, trading professional and collegiate resources and supporting and uplifting one another, in and out of the classroom. They proved that in order for Black college students to succeed, they must have equal opportunity. Because Black students were intentionally excluded from white sororities and fraternities, left out of the conversation and barely given the resources to succeed.

D9 was established by the first handful of Black students admitted into college who, in an already-segregated era, instead of waiting for a seat at the table created one for themselves. Social justice, cultural preservation and equity were at the core of D9. And the journey of the rise of these groups were nothing nice. They experienced the same racism, stereotyping, profiling and disapproval from their white peers, and there was even more of a stir specifically in Black sororities. The first Black Greek-letter sorority (and second family to our recent VPOTUS), Alpha Kappa Alpha (AKA), was founded at HBCU Howard University in 1908. They received backlash and resistance from the male-dominated, misogynistic administration in their early days of service and community organizing simply because they were women. The reality of the Black experience is sometimes (read: most of the time) a wicked paradox—it was a double-edged sword being Black and a woman.

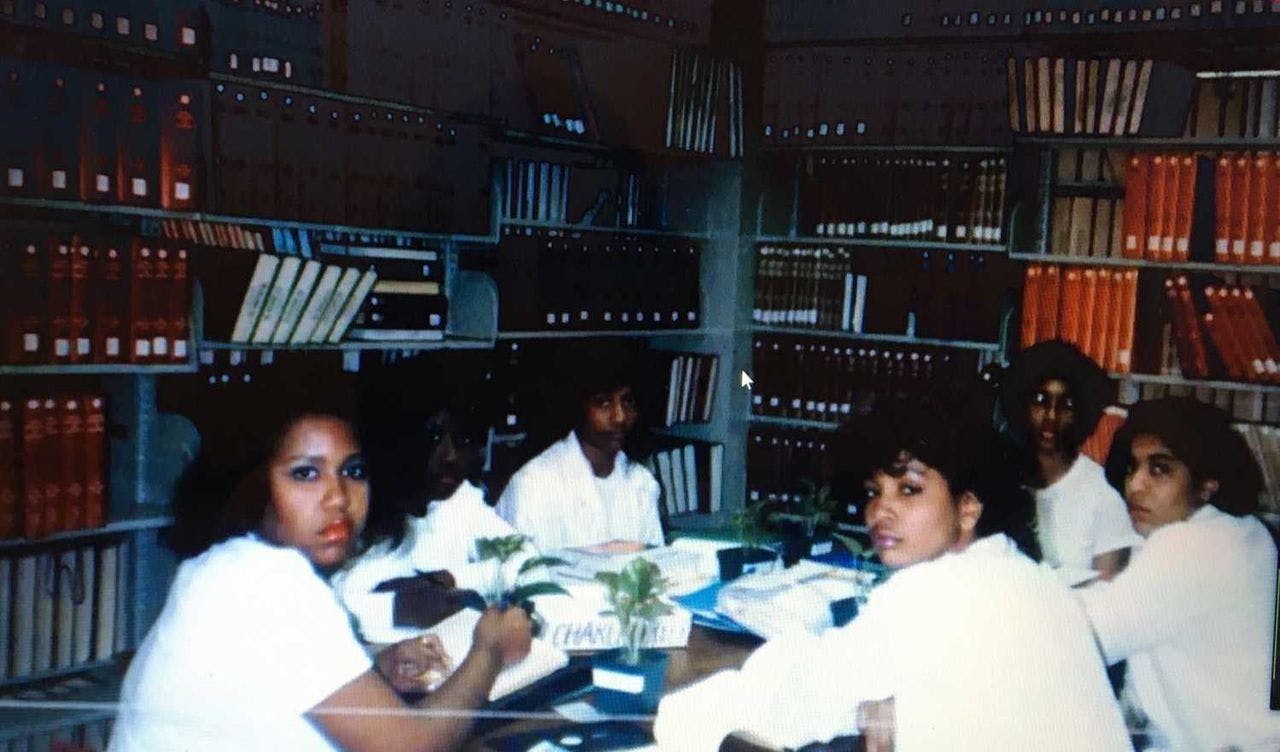

Growing up, I had a front-row seat into the life of the Black, female college experience. I come from a lineage of AKAs—my aunt, mother, sister and stepmother. And while I never pledged (sorry, fam), I watched Black women around me put in hard work, and never let up on giving back. My mother’s journey towards earning her pearls at Dillard University started with her big sister’s participation. “I admired my big sister, who was an AKA. It wasn’t a question of IF I was going to pledge, it was when. I’ve been best friends with my sisters for over 30 years. We’ve been through everything with each other, encouraged each other, helped each other out. Being an AKA can open up job opportunities and resources…because there are AKAs in every single working industry. It’s a way of servicing—nationally and internationally.” My stepmother’s experience was one of camaraderie and support at Southern University at New Orleans. “Deciding to become an AKA was very rewarding. Being the daughter of a parent who didn’t go to college, I had to figure out a path for myself. One day, I was watching School Daze, and it opened my eyes to the college experience. Of course it was an over-dramatization, but I was able to think about what I wanted my college experience to be. I went on campus for the first time at 19 and volunteered alongside different sororities so I could know what I was getting myself into. I loved the way AKA’s carried themselves, and I immediately knew that’s who I wanted to be. Once I became a member, my world opened up. I met different women from different backgrounds and walks of life. Most of the women I met, I still keep in touch with.”

Even in the middle of a pandemic, The Divine Nine continues to set the example that we can better work towards the preservation of our culture together, not apart. And according to my family, the pandemic has allowed for them to re-evaluate and redesign how they can reach people where they are. The New Orleans AKA chapter hosts virtual story time, where they purchase books written by Black authors and read them to kids via Zoom. The Houston chapter will be hosting a virtual credit-building workshop session next month. “So even in the bad,” my stepmother says, “Something good will come out of it.”

We can work towards our own success and self-preservation without limiting ourselves to approval of white faces. The Divine Nine are the OGs. They’re the ones who showed up and never let racist narratives, doubt or burden get in the way of bringing together a community with shared traditions. They show us the true divinity of community. Because there is power in love and support—received and given. There’s power in independence, self-sustainability and progress. Representation. Accessibility. And there’s self-acceptance, peace, progression and healing in honoring where we come from and loving who we are, even when people might not love us back.

The Divine Nine planted the seed of Black excellence.