Honoring The Black Midwife

Black motherhood is targeted by racist systems. Midwives can make all the difference.

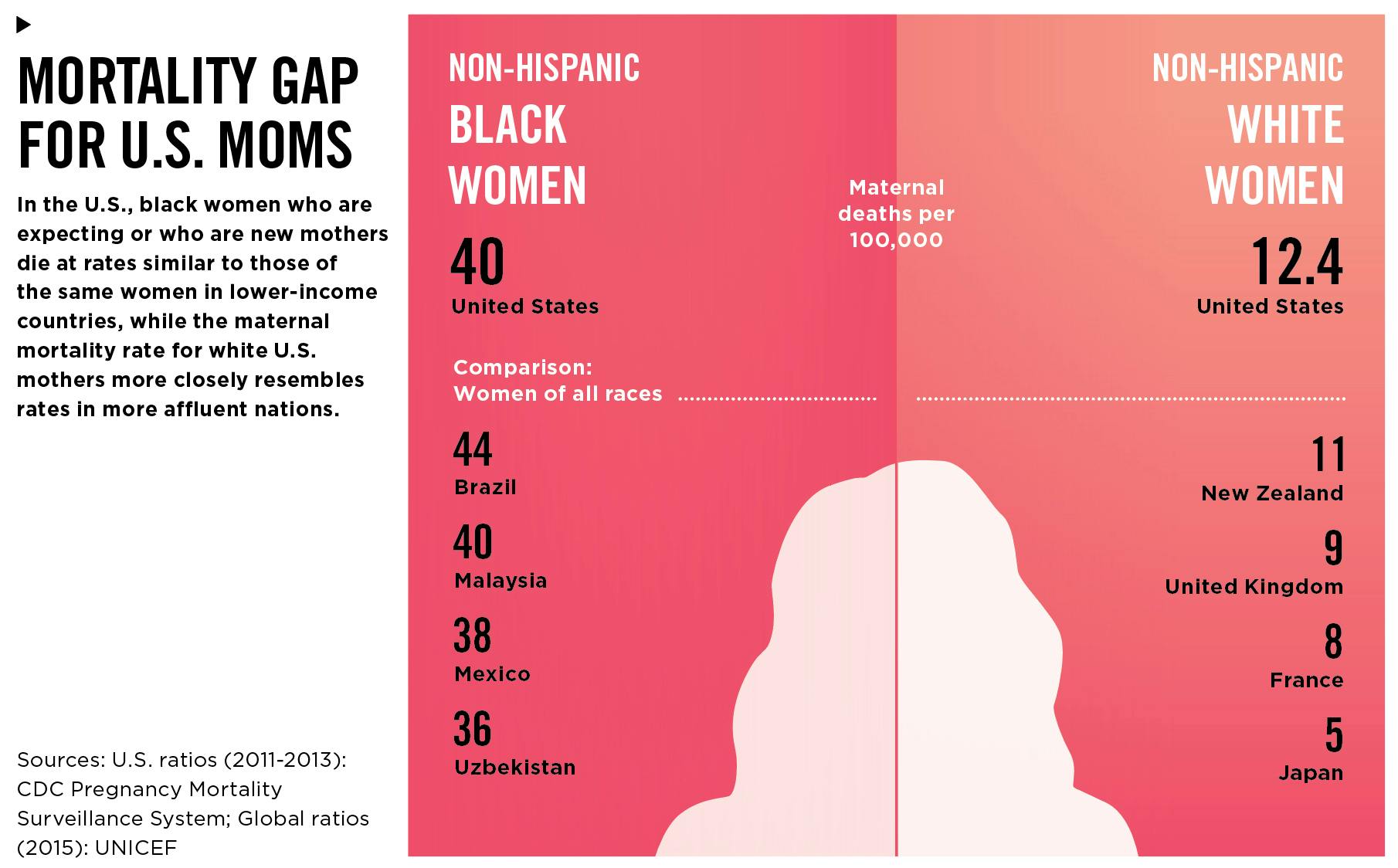

Getting through a healthy birth is a miracle for Black women. Why? Because Black women are three times more likely to die from a pregnancy complications than white women, and Black newborns are twice as likely than white babies. And to top it all off, 60% of all pregnancy-related deaths are preventable.

So that brings up questions—how can Black mothers feel safe when they’re planning to start a family? What kinds of support do they need to help them communicate to doctors and advocate for themselves during their pregnancy and postpartum? In a society of systemic racism and inequity across all industries, the idea of a Black mother not even getting a chance to be with her newborn is a tragic one. So they need an advocate with appropriate medical knowledge, cultural connection and empathy—and that’s where the Black midwife comes in.

“The practice of midwifery within the African and African American community has roots dating back to the 17th century, when Europeans brought African slave women skilled in midwifery to the United States. These enslaved women, in turn, passed on their knowledge to others.” — Honoring African American Contributions in Medicine: Midwives

The myth that midwives lack knowledge in health and safety still holds. In the early 1900s, public health reformers in the South worked hard to get rid of midwives due to the idea that infant mortality was caused from unsanitary and superstitious practices. But because of the importance of a midwife’s emotional and physical support during a woman’s pregnancy, women still sought out midwife services. So policymakers decided to compromise by providing classes and programs for midwives at local health departments.

“The 1921 Sheppard–Towner Maternity and Infancy Protection Act provided matching funds to state health departments for midwife training programs. The states established training and regulatory programs in which public health nurses taught midwives to use sterile procedures, register new births with the state, use silver nitrate eye drops to prevent gonococcal blindness, and seek physician assistance for difficult cases.” — Nothing to Work With but Cleanliness: The Training of African American Traditional Midwives in the South

In knowing the history and importance of midwives and doulas in the Black community, we wanted to get a glimpse into the lens of a midwife in modern-day medicine. Frances Coleman is a wife, mother of three children and a Licensed Midwife through the state of Texas. She runs and operates Full Circle Family Services in Houston, TX, which offers midwife care, labor doula services, yoga and educational services to families. We talked to her about her passion of being a midwife, Black maternal mortality and why it’s so important to advocate and support Black mothers.

Q: Thanks for chatting with us, Frances. Nice to meet you! Tell us who you are—what’s your background in the work you do?

A: Thank you for having me! My name is Frances Coleman, I’m 40 years old and married with three children. I’m a doula and midwife with a Bachelor’s Degree in Science and a Masters in Public Health, Health Education and Maternal Child Health.

Q: Why was it important to you to become a midwife? Walk us through the journey of how you became one.

A: My intention back then was to apply to medical school and become an OB/GYN (obstetrician/gynecologist) or pediatrician. So my desire to help families and be around mommies and babies has always been there from a very early age. I went to a majority school, and things were challenging in terms of grading. So I left and decided not to take the M-CAT, and went to grad school instead. I was accepted into Loma Linda University School of Medicine in California, and decided to get a dual-degree in Public Health, Health Education and Maternal Child Health. During my time there, I learned about maternal mortality and the differences between Black women and our counterparts—whether they be Asian, Hispanic and/or white. The disparity was ghastly. And coming from a Black family, I was shocked. I remember sitting in class thinking, “How is this white woman gonna tell me that all this is happening to Black people?” I was almost in denial. It was a hard semester for me—I was sheltered as a child, so I had a hard time processing all this information.

Once I graduated, I moved to Houston and interned at the March of Dimes, which was a lovely experience. I had a preceptor at the time who was a white woman, and she was wise beyond her years. One day, we were getting ready for a presentation on Black infant mortality and she looked at me and said, “Have you ever thought about if the system was fixed, how much money hospitals would lose? Because a lot of this stuff is fixable. But because everyone is so money-hungry, it’s the same thing every year.” That was in 2006, and the same things are still happening in 2022. What she told me that day motivated me to make a change.

After March of Dimes, I worked for Neighborhood Centers, a community center in Houston. At the time, I was part of a past program of theirs called Healthy Start, which was aimed at identifying Black infant mortality in certain communities. Then I moved on to Texas Children’s Hospital, became a certified Lamaze instructor and ran a program around health education for 7 years.

After that, I got pregnant with twins and had a traumatic experience with my birth. Unfortunately I hadn’t hired a doula or midwife for my second birth, as I did with my first. And that was a mistake—I was forced into a C-Section that I didn’t want, and it was saddening. After sitting with that and reflecting after my twins were 6 months old, I realized that I needed to be a midwife. I did my due diligence, talked to my peers in the medical space and got certified to become a midwife.

Q: Black women are the most impacted by mortality during their birth journey. Can you explain the importance of advocating for Black mothers, and how midwives are essential to protecting Black women?

A: Midwifery is such a large piece of the Black community, but also other ethnicities—it’s a large part of our community. And yet it has been so lost, mainly due to medicine and misogyny. To me, delivering babies is a woman’s job. How can a man relate to a woman growing a human being in her body, and the things she’s going through? Midwifery isn’t just about keeping mother and baby safe, it’s also about the relationship between mother and midwife. Midwifery, for me, means wearing a lot of hats and having an intimate relationship with mother and family. Not only am I a healthcare provider—but I’m a therapist, a preacher, a prayer warrior, a mediator and an advocate. I show up for my clients in the most intimate of ways. It’s about not passing judgment and working with the mother’s needs. Midwifery is all-encompassing—it’s taking care of a family. Whether it’s a new family or existing and growing family. It’s about growing that bond.

Q: What’s the difference between a doula and a midwife?

A: When people call me for a consultation, I start by telling them the difference between a doula and midwife. A midwife is a licensed, healthcare provider through the state. They have been trained through a midwifery program. A doula, on the other hand, is not licensed and provides emotional support to the family. She’s giving you additional resources, she’s reminding your partner how to show up, she’s having you think past pregnancy and talking to you about what your postpartum looks like. Your midwife does some of that, as well, but remember that your midwife is your healthcare provider. Doulas don’t have the legal responsibilities that midwives do. Midwives are liable to families and are held to a higher standard than OBGYNs. So, I could make some of the same mistakes that OBs make and lose my license. Why? Because doctors work in a system that has the money and power to make things go away. And that’s the hardest part for midwives—we have to be more careful and more intentional than OBs or our careers can be taken away a lot easier.

Q: What are some misconceptions about midwives and doulas that you hope to eliminate within your work?

A: The number one misconception is that modern-day midwives are anti-hospital and anti-doctor. That’s not true, and we’re not that ignorant. Hospitals do a great job of fixing things that are truly broken. Birth is not broken, so it doesn’t need that kind of emergency attention. But in the case that something goes wrong and it does need that attention, hospitals are essential. I also think a misconception is that the Black community thinks it’s something that is so far removed from our culture and deemed as something “only poor people do.” We’ve been taught to pull away from who we are and follow western, white, masculine ideals. I remind people all the time that OBs were never part of the original medical school program. It became that way when men came back from World War I, couldn’t get into medical school, stole midwifery practices and medicalized it, then made us look bad. OB care came from midwifery. It’s a cornerstone of Black history.

Q: In looking back at the past few years, do you find that there are more or less Black women who are interested in having a midwife during their birth journey?

A: When I first started, I didn’t see a lot of Black women interested in having a midwife during their birth journey. But now, 90% of my clientele are Black. I think there’s been a mental shift—moms don’t want to birth their baby in an environment with lots of lights, hands and people they don’t know. They don’t want to waste energy advocating for themselves and being forced into medical practices they don’t want. So Black women are starting to open their eyes. They’re hearing about infant mortality, and they don’t want to be part of the statistic.

Q: You run Full Circle Family Services—a midwifery service based in Houston, Texas. Tell us about the services you offer, how you’ve helped families and where people can find you for more information.

A: Full Circle Family Services is a midwifery and doula service, operating since 2016. We offer childbirth education, car seat installations, breastfeeding and post childbirth education and infant CPR classes. Soon, we’ll be offering support groups for breastfeeding and Black mothers. We have a small-but-fabulous team of well-versed and educated midwives and doulas. You can find more information and get a consultation on our website.

Q: What can everyone do to support, uplift and advocate for Black mothers?

A: I think what we can do to help is spread more awareness. Listen to podcasts and watch documentaries, send informational articles (ACOG) and midwife social media platforms to the pregnant or expecting women in your life. Gift someone doula recommendations for their baby shower. Help a loved one pay for a doula or midwife. And for the expecting mothers out there reading this, consider getting a doula or midwife. Just consider it.